The disappearance of an old foe leaves workers angry in its absence

Machines are normally portrayed as something threatening and potentially overpowering. Yet, it was only with the rise of the machines that people were able to boost their output enough for the bulk of society (in the West) to live in relative comfort. The combination of man and machine working in tandem also brought the middle class into existence, with the bounty of economic growth being shared relatively widely. Yet the forces that brought this about seems to have gone into reverse as both machines and the way we use them have changed, leaving many raging for times since passed.

The extent to what we could produce was limited in the past to what a person would achieve with the help of tools or farm animals. More could be harvested through harnessing the power of wind or water but the extent to which is could be applied was limited. It was only with the advent of engines powered by steam or petrol that output capacity really took off. It was not just individual workers toiling with their machines in isolation but coming together under one roof that raised labour to its most productive.

Such manufacturing enterprises offered up big gains in output per worker, especially with the shift of the population from their previous existence eking a living off the land (without the use of technology). The machinery involved was simple due to both the basic level of technology as well as the reliance on workers without technical knowledge. Over time, the machinery became more complex and increasingly required specialized skills, with demand for education rising so that workers could keep up. Pay improved as output rose (and workers banded together to demand more), but machines also developed to be able to handle an increasing range of tasks.

As such, automation enables factories to produce more while keeping labour costs down. Offshoring of production provided a different route to a similar outcome but made the change seem more dramatic as factories in the West were shuttered (instead of a gradual diminishing of employment in manufacturing that would have occurred with automation). As factory jobs became increasingly scarce, more employment shifted to the service sector where the level of technology (and hence pay) is typically low. Thus, the employment prospects of workers with low levels of specialist skills suffered due to both starting at lower levels of pay with, as described below, less opportunity for advancement.

As well as offering up higher wages for new recruits, manufacturing also allowed for workers to build up skills on the job as their knowledge of the production process expanded along with their length of employment. The production of goods would typically require a large number of different actions, and as such, the machinery would be designed with different tasks in mind. The vast division of labour into separate roles within a factory would mean that workers would develop knowledge relating to their individual sphere of work. Productivity (and hence pay) would typically rise with the length of service as more skills are learnt on-the-job.

Even in the case of workplaces in the service sector with high levels of technology (such as a logistics warehouse), the skill levels are low as machinery does much of the work. The use of software (in terms of, for example, how to fulfil an order) means that there is little scope for workers to get better at their job. It would be expected that workers could reach peak productivity within a relatively short period on the job. As well as being separated from machines, workers in the service sector also suffer from less division of labour with much of the work being similar in nature rather than specialized on separate tasks.

Any technology that is used in the service sector tends to be in the background so as to organize rather than to produce. This organization typically involves making sure that people or goods are in the right place at the right time. The limited use of technology is partly because the service sector is inherently impervious to technological improvement. Services often involve people being at the point of sale ready to act out their task when required. As such, jobs such as a waiter, teacher, or nurse would have changed but only at the margins, while the core features would remain the same.

Not only were men and machine working together in manufacturing but many people gathered in one place to work under the same roof. This higher density of workers was probably important in the formation of trade unions and demanding higher pay and better conditions. Workers in the service sector are more spread out, which, along with the limited scope for picking up skills on the job, leaves them with little leverage to get concessions from their employers. This decline in relative position is obvious in lower levels of pay for labour but also in other aspects such as shown through zero-hour contracts which gives employers more control over workers.

Not only is the predicament of service-sector workers hurting those employed in such jobs but may also be having a wider impact across the whole labour market. The lower pay for workers in service jobs also damages the job prospects of those working in other sectors of the economy as it limits the options of people to move to better jobs. Higher pay in manufacturing had been seen to boost the plight of all workers, but the switch in employment in services may be having the opposite effect.

These changes within the job market go some way to explain how employment can be high but wage gains have been weak. Even with a relatively tight labour market (such as after the Covid lockdown), increases in wages remain limited in scope (which may be in part due to an inability of employers to pass on the costs of a higher wage bill through higher prices). The shift from manufacturing to services also seems to have the effect of concentrating economic activity in larger cities with other places suffering as a result. The broad consensus regarding an open economy with free movement of goods and people was, in part, based on the economic security provided through manufacturing jobs.

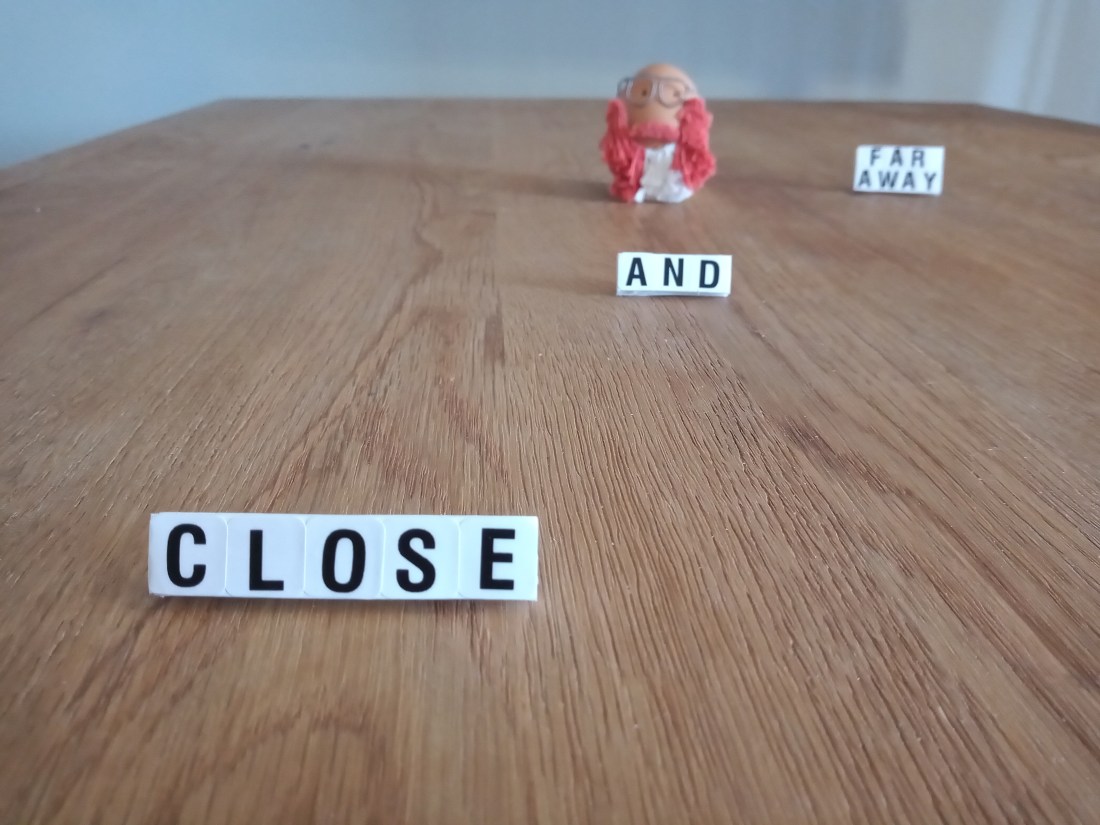

Without the relative abundance of such “good jobs”, the politics of economic growth becomes more difficult. Much about politics these days is about a return to a better past, with slogans such as “take back control” and “make America great again”. These glory days of old often involve a large manufacturing sector and all of the jobs and prosperity that comes with bring with it. Yet, the economy has changed and does not work in reverse. Even attempts to keep manufacturing jobs from moving overseas is also likely to be a lost cause as machines have reached the stage when only minimal human input is necessary for a growing number of tasks. And on top of this, the impact of a few manufacturing jobs will likely be much smaller relative to when factory work was readily available.

The focus on jobs and employment (like the emphasis on economic output) hides many of the important details. It seems to be the frustration bubbling up in politics rather than the usual economic indicators that might provide a better measure for the health of the economy. Without an understanding of what lies behind the numbers, all can seem well while the reality might be that the economy is not providing prosperity as it once did. It may be discontent, rather than data, that paints a truer picture.